Love Not Blood: Our Adoption Journey – Part 1

By Kristen Hand, CPA

Author’s Note: This article has not been easy to write. It is not a narrative about our experience navigating infertility and adoption. It is my daughter’s story – one she has yet to decide if she will share – and it is an intimate look at our family’s creation at the expense of a young woman’s pain and sacrifice. I’ve struggled with decisions about the level of detail to include, but ultimately the misconceptions surrounding adoption are too widespread and important to ignore. To protect the privacy of my daughter and her birth mother, I have omitted my daughter’s name, the state she was born in, and will refer to her birth mother as “Jane.”

************************************************************************************************

“When are you going to have kids?” is an innocent question couples are frequently asked, but one I avoid asking. For couples who have been trying unsuccessfully to begin a family, this question highlights a void in their lives and an uncertainty about their future. According to the US Department of Health and Human Services, approximately 9% of men and 11% of women have experienced infertility problems. American Adoptions claims that one in eight couples will have trouble getting pregnant or sustaining a pregnancy. Eight years ago, my husband and I became part of this statistic.

After three years of marriage, my husband and I decided to start a family. Despite our desire to become parents, each month we were left questioning if having a family would ever become reality. In October 2013, after 11 months of trying, the obstetrician ordered standard fertility tests for each of us. Those test results led to additional testing and, on a bitterly cold morning in February 2014, I barely held it together while a specialist confirmed what we had been told to prepare for: we were highly unlikely to conceive without reproductive technology. In the months prior to our diagnosis, I had been meeting with a therapist on a weekly basis to navigate the tumult of emotions I was feeling, and on occasion, my husband joined me. These meetings helped me mourn our infertility and make several important decisions. First, my husband and I decided that we would only share our diagnosis with doctors and social workers. Our stance is that WE can’t have children – we will not allow blame to be placed upon the other. We also decided that we did not want to attempt in vitro fertilization (IVF). The probability of a 60% chance of success was not high enough for us to gamble $10,000 per round. We knew from research that adoption was a potentially more expensive route depending on the number of IVF rounds necessary. However, IVF wasn’t guaranteed to end with us holding a baby like adoption would. We also knew that a family wasn’t dependent upon someone sharing our genetics. We wanted to open our hearts to a child who needed a loving home.

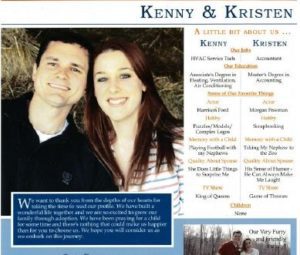

I once read an article that stated, “Adoption is not for the weak of heart. It is hard, complicated, expensive, unpredictable, and intrusive.” I have never read a more accurate statement. Our first step was to find an adoption agency that aligned with our lives. Considerations such as international vs. domestic adoption, religious preferences, financial burden, wait times, and the financial implications of interrupted adoptions (birth mother deciding to parent) had to be weighed. Luckily, one of my co-workers was on the board of directors for the Children’s Home Society of North Carolina (“CHS”), and our now CEO, Alisa Moody, had family that had adopted multiple children through CHS. These discussions encouraged me to contact our local CHS office. Because the wait times for the adoption of a newborn baby through CHS were extensive, they provided a list of five agencies that multiple home study clients had successfully adopted through. After researching the recommended agencies, we chose American Adoptions, a national agency that worked directly with birth mothers as well as smaller agencies around the country to assist matching birth mothers whose situations did not align with the smaller agencies’ prospective adoptive parents. Matching birth mothers and prospective adoptive parents is a complex system that compares a matrix of circumstances present in the birth mother’s life and the prospective adoptive parents’ comfort levels with those circumstances. After we signed our contract with the agency, we began completing an extensive and exhaustive application. The application asked typical demographic information in addition to questioning our preferences/comfort levels covering a myriad of topics:

- The child’s race (during conversations with various agencies, we learned that sadly there is a smaller demand for children who are at least partly African American)

- The child’s family medical history

- Birth defects or other medical issues diagnosed during prenatal care (operable and/or inoperable)

- The fetus’s exposure to drugs and alcohol by type and frequency

- A child conceived through rape or incest

- A child whose birth mother was HIV positive

We learned wait times for children of African American descent were shorter, and part of the adoption cost would be subsidized. This subsidy was designed to incentivize more families to consider adopting African American children. It may seem obtuse to be courted by a subsidy when discussing a child, but we were already facing tens of thousands in adoption fees and there are few, if any, couples in their mid-twenties with $30,000 – $50,000 in savings. Ultimately, we didn’t care about the color of the child’s skin; we just wanted to be a family.

I spent the better part of a Saturday researching the effects of drugs on unborn babies, by type and frequency. I read several articles that discussed not only potential physical or mental handicaps that could occur, but also the excruciating withdrawal symptoms newborns experience. The range of emotions I felt while reading this ranged from despair and heartbreak to rage. I asked, for the thousandth time during those many months, why a woman addicted to drugs and one who would impose such pain on a baby could get pregnant but thousands of stable, loving couples could not.

I spent the better part of a Saturday researching the effects of drugs on unborn babies, by type and frequency. I read several articles that discussed not only potential physical or mental handicaps that could occur, but also the excruciating withdrawal symptoms newborns experience. The range of emotions I felt while reading this ranged from despair and heartbreak to rage. I asked, for the thousandth time during those many months, why a woman addicted to drugs and one who would impose such pain on a baby could get pregnant but thousands of stable, loving couples could not.

The last, and most complex, part of the application was determining our “budget.” Adoptions can range in cost depending on the birth mother’s living, medical, and legal expenses. For instance, a birth mother’s living expenses in California would exceed those of someone living in Alabama. Factors other than residency that could affect costs included other children in the home, government subsidies for housing, food, medical insurance, special medical needs surrounding the pregnancy, and state laws governing the adoption process. Once matched with a birth mother, the prospective adoptive parents begin paying the birth mother’s living, medical, and potential legal expenses. Often if a match is disrupted (the proper term for a birth mother “changing her mind”), the prospective adoptive parents are left with a financial loss in addition to the emotional heartache. One of the principal reasons we selected our agency was being able to insure ourselves against any potential financial loss. After several conversations with the agency about historical data and a full breakdown of our budget, we set our maximum budget at $33,000.

The application process was a way for the agency to determine in what circumstances a match could be made, however the agency was required to determine whether we were fit to be parents. Imagine coping with the emotions of infertility, funding an adoption, and opening your life to strangers to examine every aspect of your life with a microscope.

We had to fill out basic information, supply bank statements, tax returns, current pay stubs, a complete breakdown of our income and expenses, our plan for financing the adoption, and a copy of our marriage license. We were required to request eight trustworthy and long-term friends and colleagues to write recommendations on our behalf and have full medical exams completed to determine our health level. We were asked a myriad of questions, some of which were asked orally during our home visit, and some of which were asked as part of our application:

- How were you punished as a child? How do you plan on punishing your child(ren)?

- What were you taught about sex and what do you plan on teaching your child(ren)?

- What do you consider your greatest accomplishment?

- How have you mourned your infertility diagnosis?

- Who is your biggest parental role model?

- How many firearms are in the home? How are they stored?

- What is your guardianship plan in the event of your untimely death?

- Describe the communication in your childhood home.

- Describe the relationship you have with each member of your immediate family.

- Describe your parents’ marriage and how it has impacted your view of marriage.

We were also required to submit to the following record and background checks:

- State and national criminal record check through the SBI

- North Carolina and FBI national sex offender registries

- Search through the Automated Child Welfare Information System for any history of child abuse or neglect

The days prior to our home study were a whirlwind. I cleaned every square inch of our house – no closet, drawer, or cabinet was left unturned. We installed carbon monoxide detectors and additional smoke detectors. We bathed and groomed our dogs. I was a nervous wreck before the first of our two home visits. However, our social worker could not have been nicer, and once we began our interviews (we were interviewed individually and together), the majority of my anxiety melted away. She not only looked around the house and interviewed us, but gave us advice on ways we could prepare ourselves and things we needed to be aware of once the agency contacted us about a match – one of those was making sure we began educating ourselves on transracial adoption (a subject that I strive to continue learning about). The resulting home study report was a fourteen-page narrative of the most intimate details of our lives before providing a recommendation. The last paragraph begins with: “The Hands are a warm and committed couple. They are thoughtful, intelligent, and have gone about the adoption process with deliberation and characteristic motivation. They are supportive of one another and in agreement in all decisions they have made about the adoption process. They are emotionally stable, have a strong moral foundation, are physically capable, and financially stable enough to provide for all areas of need in a child’s life. It is recommended that [they] be approved for adoptive placement of a domestic adoption of a male or female newborn…”

During this time, I was also counseled by both of my social workers to avoid having a baby shower for a particular match. If the match was disrupted, we as the adoptive parents would have a nursery full of items associated with that lost child. I thought I could circumvent potential negative feelings about a baby shower if the shower was held before we became an active waiting family. I could not have been more wrong. While I was, and remain, grateful to those who supported us at the shower, I could not wait for everyone to leave. There I was, opening up all of these gifts for a child I didn’t know if I would ever have. As soon as everyone left, I piled the gifts in the corner of the “completely empty nursery,” shut the door, and did not open it again until we were matched.

In June of 2014, four months after we started the adoption process, the home study had finally been completed and approved by the adoption agency and we became an active waiting family. Each day, I awakened wondering, ‘is this the day I get the call?’ During the wait, we were contacted about a couple of different situations that involved a child with long term medical or special needs. I do not exaggerate in stating that I questioned the kind of person I was when replying “no, we aren’t interested” to those emails. Those decisions were painstaking, and we discussed each at length, but we couldn’t commit to something we did not feel we were capable of handling.

Three weeks after we became active, we received a call from a social worker who was working with a birth mother in the Midwest who was scheduled to give birth via a c-section in eight days. The difficulty with the match was that the expected expenses were $7,000 over our budget. We had already taken the loan from our 401(k) because we knew that we would have to wire the majority of the fees to the agency within 24 hours of a match (several had been paid up front for specific things like the application, home study, and marketing fees). Initially, we had no intentions to tell anyone about the match with the exception for our bosses and our dog/house sitter in the event the match was disrupted. Unfortunately, under the circumstances we had to make some phone calls to put together the rest of the funds. Despite the match being above our budget, the timing couldn’t have been more perfect. BRC reduces required hours during the summer based on workload, and the additional four hours per week helped extend my paid leave. As we were facing the huge price tag of a $40,000 adoption, I couldn’t afford to take any unpaid leave. That night we had a conference call with Jane, and it was the most awkward conversation I’ve ever had. I could only say thank you so many times and it seemed an insufficient thing to say to someone who was giving me the greatest gift. I was terrified of saying the wrong things despite being coached by the social workers. There were awkward silences and speaking at the same time trying to fill those silences. We were able to learn more about her life and told her more about ours; she told us what she would name the baby for herself and asked what we would name her – after answering, she said she felt it was a sign that this was the right match and explained the personal reason she felt it to be a sign.

It had been Jane’s wish to meet us for dinner the night before the c-section, not only to get to know one another more, but to make the meeting at the hospital less awkward. If you’ve ever felt nervous going into a job interview, imagine the nerves involved going into an “interview” asking not for a job, but for someone to place their unborn child into your care. Dinner with Jane and her cousin went well. She and I asked a lot of questions and shared stories about our lives. Jane shared in detail with us the reason behind placing the baby for adoption and we described to her why we had chosen adoption. That night at the hotel, neither my husband nor I could sleep. We were so full of anticipation for what the next day would hold.

Part 2 of this article will be published after the new year.